Ever since I saw the film Sicilia! (1998) by Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub I have wanted to return to Sicily. It is inspired by the book by Elio Vittorini, Conversazione in Sicilia (1941), which I read in French as Conversation en Sicile. I saw the film in France too, at the end of October 1999, in the Studio des Ursulines in Paris (the ticket stub is in the book; sometimes the internal archivist gets it exactly right). It starts with the protagonist sitting in a train going along the coast from Messina to Palermo, it is in black and white, the train is old, the windows are open, and he and his fellow passengers converse in a strange declamatory style. I seem to remember curtains fluttering at the open windows of the train, and views of the sea, as if the railway line ran right beside the shore. The protagonist is returning home after a long absence and there are many things about his home that he has forgotten.

We were there nearly twenty years ago, for too brief a time, and hardly saw anything, so obviously I had to go back. Actually what I wanted was to take that train myself, and I did, but of course it is just an ordinary train now, useful for going from Palermo to Bagheria and Cefalù, and the view of the sea is often obscured by concrete. Still it provided a definite frisson, especially when listening to the other passengers’ incomprehensible accents. One of the many ways in which Sicily comes as a shock is that the people don’t seem to be speaking Italian at all; in fact Sicilian is considered a separate language, with elements of the languages of all those who colonised the island, from Greek and Latin to Arabic, French and Spanish. The architecture has all those elements too, from Greek temples to Arab-Norman churches.

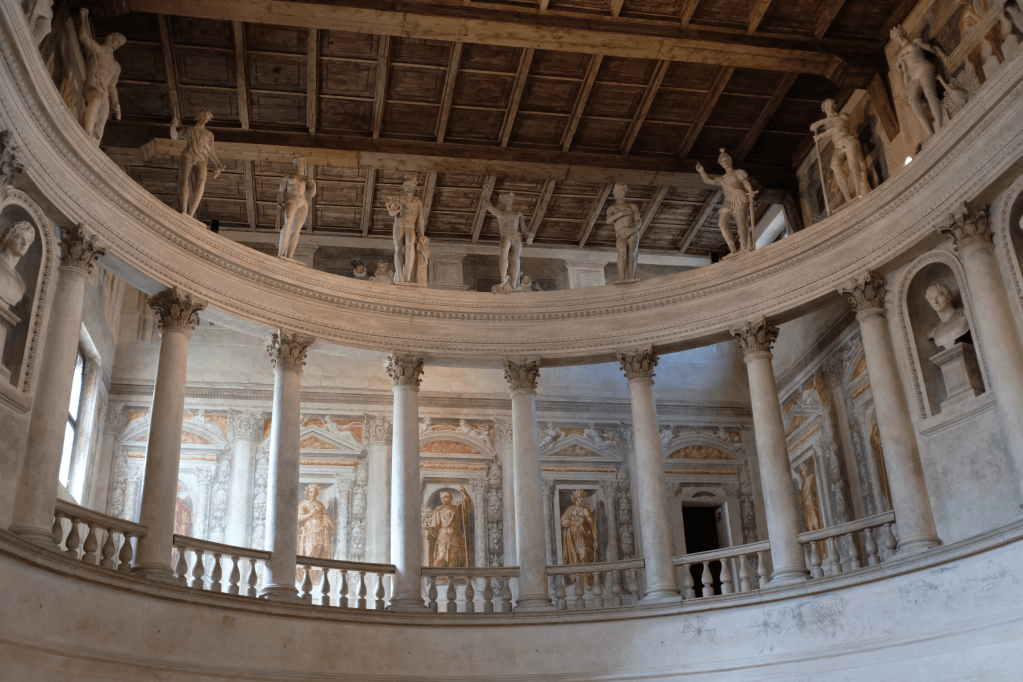

There is a lot to see in Palermo, and there are an awful lot of tourists, large groups being herded around, mostly to the places where there is no admission charge; if you are willing to pay to get in, to a cloister or a baroque chapel, you can be free of them. They also gather, with buskers and loudspeakers, at the beautiful Quattro-Canti crossroads. I remember how years ago we gasped with surprise when we saw it as we drove into the city; it looked like a stage decor. Hurrying away from the music I ducked into a church and saw two fantastic marble angels holding out gilded stoups, one on each side of the door.

My English guide book had a hectoring tone, with many imperatives – Swoon! Grab! Mooch! Devour! – and was fairly inadequate. Its Italian version (with restful verbs in the infinitive) was better. I went to Monreale in a very crowded bus, saw one half of the Palatine Chapel, as the other half is being restored, and devoured a giant – and extremely sweet – cannolo in a convent garden. I passed the Grand Hotel et Des Palmes several times before reading that Wagner had stayed there, then went in and asked: indeed that is where he wrote Parsifal and his piano is still in the presidential suite. There is a plaque to him at the back of the hotel. Later, in a museum in the town of Castelbuono, I saw an oddly moving artwork by Olaf Nicolai about the writer Raymond Roussel, consisting of photos of the soap he would have used during his last days on earth, spent in the Grand Hotel et Des Palmes. He killed himself there in 1933. There is no plaque for him.

Abandoning the baroque in favour of Arab-Norman buildings brings you into an emptier and less polished part of the city, originally part of the Royal Park, the Genoardo, from Gennat-al-Ard or ‘Earthly Paradise’, founded by King Roger II (r. 1130-54). This was a hunting ground, farmland and pleasure grounds and some of its buildings still survive, first the amazing Zisa Palace, begun in 1165, a massive building in the Islamic style, with a central hall with mosaics, where water would have trickled down through two basins, extremely thick walls, long corridors and a system of internal air vents for hot days. ‘Nowhere does Norman Sicily speak more persuasively of the Orient; nowhere else on all the island is that specifically Islamic talent for creating quiet havens of shade and coolness in the summer heat so dazzlingly displayed’ (John Julius Norwich, in The Kingdom in the Sun). It has been restored, and I wandered around almost alone, marvelling at its curious architecture, amazed that it had survived at all.

Then I went down the Corso Calatafimi (also originally an Arabic name), the road to Monreale, with almost empty buses taunting me, unlike the packed one I took to get there myself. There was a 17th century fountain, still functioning, behind bars. Between the more recent buildings were large 17th and 18th century buildings, one now a school, another previously a home for the poor, and then there was the Cuba, another huge rectangular building, built in 1180 by William II in the royal park. In the past this was in a barracks; in On Persephone’s Island Mary Taylor Simeti describes having to get a permit to see it. Now some people who look as if they have just disposed of their predecessors’ bodies sell you a ticket and you enter, again completely alone, a building that was once surrounded by water, and that seems to have been dedicated only to pleasure. It is high and roofless, with muqarnas like the Zisa, and even more than the latter calls up Ozymandias: ‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings./ Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ The Arabic text along the roof is along the same lines: ‘… Stop and look! See the great room of the greatest of all kings on earth, William II. No castle exists that is worthy of him…’

Further along the road and up a side street is the friendliest and smallest of all these buildings, the Cubula. It too is behind bars, in a large garden, part orchard full of lemons and medlars, and is, according to the guidebooks, closed. They had both often been wrong, so I walked all the way up to the end, where some workmen were sitting on plastic chairs, about to tidy up the garden. I could go in, they said, so I set off down the path, past the spectacularly decaying 17th century Villa di Napoli and through the jungle of trees and shrubs, all the way down to this tiny pavilion with its little red dome.

There would be just room for two people to sit in it, for a moment’s respite on a hot day, and despite the blocks of flats around it no reading or description could give you more the feeling that you have stumbled into the Earthly Paradise of the Norman kings of Sicily.

Looking back I took a photo of the side of the Villa, but it was only when looking at the photo later that I found the traces of one more Arab-Norman building, the Cuba Soprana. So I saw that too. Then, walking back towards the city and modern life I passed, on a corner of one of the side streets, a man with a crate and plastic buckets. I stopped to look: he was selling snails, and bunches of wild chicory. Here too I didn’t realise what I had seen until I was home again, wondering if I would ever do anything at all if I hadn’t first read about it or seen it in a film, and started rereading Conversation en Sicile.

In the second part, when the protagonist reaches his mother’s house they talk about the past, and his childhood. He doesn’t remember that they sometimes went hungry; on the last twenty days of the month, his mother says, once their father’s pay had all been spent. And then she says, ‘We ate snails.’ ‘Snails,’ I said. ‘Yes,’ said my mother, ‘and wild chicory (…) That is all the poor had to eat.’